Abigail Jane Scott was born in a log cabin on October 22, 1834, on the frontier of Groveland Township, Tazewell County, in central Illinois, a few miles from Fort Peoria.1 She was the second daughter and third child of Ann Roelofson Scott2 and John Tucker Scott3, to whom nine more children (five daughters and four sons) would be born.4 In 1852, when Jenny5 was 17, the Scott family joined the largest migration to Oregon in American history.6 Her mother and a brother died en route. The others arrived in French Prairie in the fall, joining relatives who had preceded them, and settled near Lafayette, in Yamhill County, shortly thereafter.7 In the spring of 1853, she opened a school in Cincinnati (now Eola), near Salem. On August 2 of that year, she married a handsome young rancher, prospector, and horseman named Ben Duniway8, settling on his donation land claim in the heavily forested hill country of Clackamas County. For nine years she endured the hardships and toil of a farmer’s wife, including five in the “Hardscrabble” region, where their first two children were born: their only daughter, Clara Belle (May 26, 1854-January 21, 1886), and the first of five sons, Willis Scott (February 2, 1856-August 5, 1913). In 1858, Ben bought a farm in Yamhill County, which Abigail dubbed “Sunny Hillside.” Here two more sons were born: Hubert Ray (March 24, 1859-November 28, 1938), and Wilkie Collins (February 13, 1861-May 30, 1927).

In the autumn of 1862, in what her chief biographer calls “the turning point in the Duniway marriage,” their farm was sold to settle the bad debts of a man whose notes Ben had co-signed.9 The Duniways moved into a small house in Lafayette, where Abigail opened a boarding school and Ben took a job as a teamster. Then a second tragedy ensued: Ben was run over by a team of horses pulling a heavy wagon, rendering him an invalid. In 1865, Abigail sold her school and the family moved to Albany, where she ran another school for a year and then opened a millinery shop. Two more sons were born in Albany: Clyde Augustus (November 2, 1866-December 24, 1944) and Ralph Roelofson (November 7, 1869-December 7, 1920). Some months after the Fifteenth Amendment, declaring that “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged . . . on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude,” was ratified in 1870, she and two friends organized an equal suffrage society there.10 In early 1871, she moved the family to a small rented house in Portland and began to campaign for woman’s rights in earnest. Susan B. Anthony and she organized the Washington Woman Suffrage Association while canvassing in Olympia that year.11 She organized the Oregon State Woman (later Equal) Suffrage Association in early 1873.12 In 1883 the Washington territorial legislature passed a measure, drafted by Abigail, that granted the vote to women. From 1887 until 1895, she summered on a ranch in the Lost River Valley in south central Idaho, which sons Willis and Wilkie had purchased in part for speculative purposes and where Ben raised horses and cattle. The groundwork she laid played an important part in that state’s adoption of woman suffrage in 1896. In Oregon, after five unsuccessful campaigns (1884, 1900, 1906, 1908, and 1910), victory finally came in 1912. Abigail died on October 11, 1915.

Even an account as brief as this is central to understanding Scott Duniway’s persuasive efforts, which–sometimes explicitly, often implicitly–drew heavily on her life experiences.13 Scott Duniway is an especially noteworthy advocate for two fundamental reasons.

Her Rhetorical Corpus

First, Scott Duniway’s corpus of speeches and writings is remarkably large and diverse. Among women of the period, only Charlotte Anna Perkins Stetson Gilman’s varied and extensive oeuvre rivaled Abigail’s.14

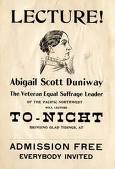

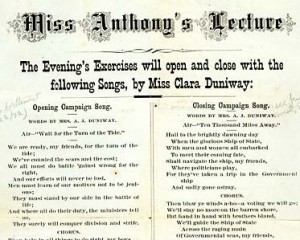

There is Scott Duniway the orator. She cut her teeth on the lecture circuit during Susan B. Anthony’s thousand-mile speaking tour of Oregon and Washington in 1871, for which Scott Duniway was business manager and delivered speeches of introduction.15  Thereafter, she stumped her “chosen bailiwick” of the Pacific Northwest herself, organizing local suffrage associations across Oregon, Washington, and Idaho, and canvassing for her woman’s rights newspaper. She divided the first twelve and one-half years of her efforts equally between Oregon and Washington, estimating that she delivered 70 speeches in each place every year, or a total of 1,750 addresses from 1871 (when her equal rights newspaper, the New Northwest was launched) to 1884 (when Oregon’s first equal suffrage referendum took place.) She also was the chief advocate for woman’s rights in Idaho for nearly twenty years; her work there, she estimated, involved 140 public lectures and 12,000 miles of travel from 1876 to 1895. In 1886, she reported walking five miles every day of the year (except Sunday) to collect subscriptions, writing one hundred pages of manuscript each week, and delivering three to four public lectures per week.16 She also lectured throughout northern California, and in states across the country (including Illinois, Iowa, Wyoming, Utah, Michigan, Minnesota, and Ohio) on her way to and from the national suffrage conventions.17 She participated actively in related reform organizations, including temperance alliances18 and woman’s clubs19. Five-foot-six, stocky, possessing a “wondrous deep contralto voice” that sounded almost Biblical, even into old age, unflagging, articulate, and assertive, she made a strong impression.20 She was “a forceful, logical platform orator, with a touch of sarcasm and a dash of humor that make her arguments effective. As an impromptu speaker she has few equals.”21

Thereafter, she stumped her “chosen bailiwick” of the Pacific Northwest herself, organizing local suffrage associations across Oregon, Washington, and Idaho, and canvassing for her woman’s rights newspaper. She divided the first twelve and one-half years of her efforts equally between Oregon and Washington, estimating that she delivered 70 speeches in each place every year, or a total of 1,750 addresses from 1871 (when her equal rights newspaper, the New Northwest was launched) to 1884 (when Oregon’s first equal suffrage referendum took place.) She also was the chief advocate for woman’s rights in Idaho for nearly twenty years; her work there, she estimated, involved 140 public lectures and 12,000 miles of travel from 1876 to 1895. In 1886, she reported walking five miles every day of the year (except Sunday) to collect subscriptions, writing one hundred pages of manuscript each week, and delivering three to four public lectures per week.16 She also lectured throughout northern California, and in states across the country (including Illinois, Iowa, Wyoming, Utah, Michigan, Minnesota, and Ohio) on her way to and from the national suffrage conventions.17 She participated actively in related reform organizations, including temperance alliances18 and woman’s clubs19. Five-foot-six, stocky, possessing a “wondrous deep contralto voice” that sounded almost Biblical, even into old age, unflagging, articulate, and assertive, she made a strong impression.20 She was “a forceful, logical platform orator, with a touch of sarcasm and a dash of humor that make her arguments effective. As an impromptu speaker she has few equals.”21

Also, there is Scott Duniway the journalist. As a young wife and mother, “Jenny Glen” began writing to the Oregon City Argus in 1855 and, as “A Farmer’s Wife,” to the Oregon Farmer in 1859. She also was writing frequently to the Salem Statesman by this point.22 At this early stage Abigail disapproved of equal suffrage, writing that “women in some places are claiming rights they should not have.”23 While complaining about the hardships that accrued to married women on account of their inferior position, she nonetheless advised: “‘Ardent ladies’ may wish to control affairs of church or state, but what I want is to see ladies content . . . to use cradles for ballot boxes in which they have a right to plant, not votes, but voters.”24

Within a few years, however, Abigail had crossed the Rubicon.25  Following a trip to California in late 1870, she became Oregon editor of the San Francisco-based, short-lived Pioneer, Emily Pitts Stevens’ woman’s rights paper.26 In May, 1871, shortly after coming to Portland, she launched her own weekly, the New Northwest, which she edited and published (with substantial help from her family) for sixteen years.27

Following a trip to California in late 1870, she became Oregon editor of the San Francisco-based, short-lived Pioneer, Emily Pitts Stevens’ woman’s rights paper.26 In May, 1871, shortly after coming to Portland, she launched her own weekly, the New Northwest, which she edited and published (with substantial help from her family) for sixteen years.27

Scott Duniway’s journalistic career did not end with the New Northwest’s sale in 1887.28 She was associated with the Coming Century, a short-lived monthly about which little is known.29 At the same time, for its final few months in 1891, she was a major contributor to the West Shore. Founded by Portland publisher Leopold Samuel30 in 1875, the West Shore was the first illustrated publication west of the Rockies.31 When the West Shore Publishing Company was reorganized in September, 1890, and Samuel retired a few months later, Scott Duniway entered the scene.

Seeking the improved profitability that higher circulation would bring, the new management announced, in the February 7, 1891, issue, that the periodical’s “style and character will be materially changed.” Abigail’s first column, regarding a Multnomah County consolidation bill, appeared the following week.32 On February 21, in addition to the first of a two-part column on “Hobby Horses and Their Riders,” the publishers announced that Scott Duniway was leaving for the National American Woman Suffrage Association (N.A.W.S.A.) convention in Washington, D.C., that she would “represent” the West Shore, and promised: “Her racy letters will appear regularly in our columns during her absence.” Appear they did, sandwiched between other contributions over seven subsequent weeks.33 Then, on April 18, an even larger role was heralded:

Beginning with this number of the WEST SHORE, Mrs. A. S. Duniway will conduct a department in which the cause of womankind, politically, socially, and morally, will be a prominent feature. . . . Her work will be a regular feature of the paper, and so conducted as to be fair but vigorous always. The WEST SHORE offers this as one of the elements which make a public journal influential. This department is made possible by the addition of four pages to the size of the paper, and we are confident that the work will add to the interest of the paper among the people at large.

This new department debuted with an impressive graphic (a ribbon bearing Abigail’s name flanked by ribbons of Justice, Equality, Liberty, Society, Art, Home, Business, Literature, and Fashion), her “Salutatory,” and a variety of other material. The following week featured a speech by Anna Howard Shaw, letters from several suffragists across the country, and announcement of plans to revive the Oregon State Woman Suffrage Association (Abigail also was profiled elsewhere, in a column called “Prominent People of the Pacific Coast”).

Then, almost as suddenly as it had begun, the new venture ended. With the issue of May 2, 1891, Scott Duniway’s department, and the West Shore itself, ceased publication. Resilient in all things, Abigail resurfaced four years later as editor of the Pacific Empire (1895-1897).

Throughout her career as a journalist, Scott Duniway faithfully attended sessions of the legislature, reporting on its doings, lobbying, and, on occasion, speaking.34 When on the stump, she would send editorial correspondence, a combination of travelogue and biting commentary, for publication. She appeared in the columns of other equal suffrage organs, including Susan B. Anthony’s, Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s, and Parker Pillsbury’s Revolution, Lucy Stone’s and Henry Blackwell’s Woman’s Journal, and Clara Bewick Colby’s Woman’s Tribune.35

Abigail also wrote countless letters to the editors of other newspapers throughout the region. Her dealings with the powerful Oregonian were particularly nettlesome because it was edited, for more than forty years, by Harvey Whitefield Scott36, who disagreed with his older sister about woman suffrage and other issues.37 The two were sibling as well as journalistic rivals, and their well-publicized encounters over the years ran the gamut, from laudatory to considerate, to testy, to downright hostile.38

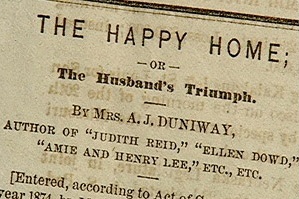

Finally, there is Scott Duniway the littérateur. She published a bit of “poesy” in the Illinois Journal at the age of 16 and continued to write verse all her life. “The Burning Forest Tree,” written “on a lonely ranch in the wilds of Clackamas County” in 1854, was contributed to the Oregon City Argus in 1857.39 “Thoughts in Storm and Solitude” was published in 1868, and “After Twenty Years” in 1872.40 She self-published a collection entitled My Musings in 1875 and the epic poem David and Anna Matson one year later.  Abigail’s poetic impulse also often found secondary outlets in the lyrics of pro-suffrage songs and–-as this archive reveals–-in lyrical prose, vivid metaphor, colorful imagery, and actual verse in her public addresses. Poetry possessed an elevated status in the nineteenth century: No mere fancy or ornament, it often was used to convey, in condensed, emotive form, the essence of an idea, that is, to encapsulate a truth. While rare today, several of Scott Duniway’s speeches incorporate extended verse, usually at their conclusion (like perorations, the better to crystallize her message). In addition, over forty-six years, Abigail authored twenty-two didactic novels, most written week-to-week under pressure of deadlines and serialized in her newspapers, with heroines whose lives bore a striking resemblance to her own and taught lessons bearing on “the woman question.”

Abigail’s poetic impulse also often found secondary outlets in the lyrics of pro-suffrage songs and–-as this archive reveals–-in lyrical prose, vivid metaphor, colorful imagery, and actual verse in her public addresses. Poetry possessed an elevated status in the nineteenth century: No mere fancy or ornament, it often was used to convey, in condensed, emotive form, the essence of an idea, that is, to encapsulate a truth. While rare today, several of Scott Duniway’s speeches incorporate extended verse, usually at their conclusion (like perorations, the better to crystallize her message). In addition, over forty-six years, Abigail authored twenty-two didactic novels, most written week-to-week under pressure of deadlines and serialized in her newspapers, with heroines whose lives bore a striking resemblance to her own and taught lessons bearing on “the woman question.” 41 Captain Gray’s Company, or, Crossing the Plains and Living in Oregon, based on the diary that she had kept during her own family’s crossing, was the first commercially printed novel in Oregon, in April, 1859.42 Abigail believed that allegorical fiction was her most effective medium.43

41 Captain Gray’s Company, or, Crossing the Plains and Living in Oregon, based on the diary that she had kept during her own family’s crossing, was the first commercially printed novel in Oregon, in April, 1859.42 Abigail believed that allegorical fiction was her most effective medium.43

Her Rhetorical Choices

Scott Duniway also is notable as a western, pioneer feminist. Studies of the nineteenth-century woman’s rights movement have concentrated on eastern feminists and suffrage campaigns in the more settled states.44 But conditions in the west were different, and many western feminists believed their rhetorical situation to differ from that of their eastern sisters. Many subscribed to a notion that might be called western exceptionalism, believing that the spirit of freedom, independence, perseverance, and self-reliance fostered by the pioneer experience was unique. It followed that conditions in the west favored progress and that frontier audiences were especially amenable to certain appeals and particularly averse to others. Moreover, the west was strategically different, feminists thought, because it was easier to shape law in a new land than it was to overturn settled law and “tyrant Custom” in the east.45 Hence, rhetors like Scott Duniway looked for their models to the discourse, ideals, and values of the American Revolution, when the United States itself was new. She protested vociferously, frequently, and often undiplomatically, against “interference” in regional efforts by “imported” workers from “the National,” whose eastern tactics she often blamed for the failure of campaigns in the Oregon Country. Finally, as her territory came to resemble the settled east, its frontier origins increasingly distant, she strove to maintain the salience of her message by recreating the pioneer experience in historical narrative. Hence, her rhetoric differs from the discourse of other, better known advocates, and these differences shed important light on the diversity of, and tensions within, the nineteenth-century woman’s rights movement.

Deliberation

Aristotle first codified the types of oratory, reflecting those speaking situations that were central to classical culture. Deliberative speaking was the discourse of the Athenian assembly, in which citizens debated matters of public concern. Because its object was choice among alternative policies, deliberation addressed the desirable and undesirable; because choice would determine the polis’s direction, it was future-oriented.

In an obvious sense, much of Scott Duniway’s rhetoric, which addressed the merits of equal rights, was of this kind and confronted nineteenth-century barriers to women’s participation in public deliberation. Like many others, Abigail noted the unique obstacles to women’s advocacy posed by the “unwomanly” character of the public podium.46 At the same time, she was acutely aware of the sense in which women’s only power was rhetorical. Women could not enfranchise themselves; they could obtain their rights only by the hand of men. It followed indisputably, Scott Duniway believed, that women should take care not to antagonize men or give them cause to fear women’s enfranchisement, and should appeal only to men’s noblest instincts. In “How to Win the Ballot” (1899), she analyzed women’s rhetorical situation and prescribed her approach:

The first fact to be considered, when working to win the ballot, is that there is but one way by which we may hope to obtain it, and that is by and through the affirmative votes of men. . . . we must show them that we are inspired by the same patriotic motives that induce them to prize it . . . [and] impress upon all men the fact that we are not intending to interfere, in any way, with their rights; and all we ask is to be allowed to decide, for ourselves, also as to what our rights should be.

This understanding dictated Scott Duniway’s persuasive choices. She invoked “the great principles” of liberty and justice articulated in the U.S. Constitution and Declaration of Independence in promotion of human, not strictly woman’s, rights.47 She echoed patriots from the Founding Fathers to Lincoln. She repeated the common but controversial suffragist argument that the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments had extended the franchise to women.48 And she invoked the catch-phrases of the nation’s birth. “Government by consent of the governed,” she contended, remained a mockery so long as women, who clearly were numbered among the governed, could neither grant nor withhold their consent via the ballot. Similarly, “taxation without representation,” she cried, “is tyranny.”49 Her 1877 address to the Illinois legislature, on “Constitutional Liberty and the ‘Aristocracy of Sex,’” is a classic statement of these principles.50

While these themes were common in suffragist advocacy of the day, few pursued them as single-mindedly as Scott Duniway, who strenuously resisted expediency-based rationales, or claims that women ought be enfranchised because of the desirable outcomes of women’s participation in politics.51 Principled appeals to human rights emphasize the degree to which men and women are alike, that is, their common personhood, while expediency appeals emphasize their differences, that is, women’s womanhood.52 In practice, the latter have tended to be more conservative insofar as they accept the premise of difference that underlies the rationale for a restricted “woman’s sphere” (even if this sphere is eulogistically covered as the “pedestal” to which women are “elevated”), while the former have tended to be more radical insofar as they contest the very bases of difference. In a society that accepts that men and women are different (biologically, theologically, sociologically, or otherwise), expediency arguments may hold greater appeal, but at the considerable price of reinforcing confining stereotypes. So it should not surprise that the choice between these two forms of argument bedeviled advocates. Among nineteenth-century suffragists, roughly speaking, the choice divided the wider feminism of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, et al., from the more limited, “suffrage only” efforts of Lucy Stone, et al., and–-from 1869 until 1890, when the two organizations merged–-the National and American Woman Suffrage Associations.53

Although she flirted with expediency arguments early in her career, Scott Duniway rather quickly came to reject them in favor of principled arguments for human rights.54 Addressing the Oregon State Equal Suffrage Association (O.S.E.S.A.) in 1897, she declared:

We have from our first existence as an association demanded our right to vote because it belongs to us by every sacred right vouch-safed to every citizen of the United States through the [D]eclaration of Independence and the Federal Constitution. We make no pledges as to what we will do or will not do with the ballot when we get it. Women differ as widely over side issues as do men.

Railing against the “one-idead,” she steadfastly maintained that suffrage ought not favor any particular “ism.” Her presidential address at O.S.E.S.A.’s 1909 convention declared:

Our platform is strictly non-partisan and nonsectarian. It welcomes to its standard every Jew and Catholic, Protestant and Mormon, Christian Scientist, Spiritualist, Theosophist and Pagan who will support our plea against taxation without representation. It appeals for support at the polls to every Democrat, Republican, Prohibitionist, Socialist, Anti-Prohibitionist, Anarchist and Union Labor partisan.55

Scott Duniway reserved the greatest measure of her ire for the White Ribboners of the W.C.T.U. Although a lifelong temperance advocate, she appears to have abandoned her early advocacy of prohibition by 1881.56 In principle, she came to believe, women could not seek rights for themselves and simultaneously seek to deprive men of theirs. Prohibition qua prohibition, whether of the liquor traffic or of women’s right to vote, was wrong. In a letter to the Oregonian on October 13, 1887, she wrote: “The two ideas of prohibition and liberty are in exact juxtaposition to each other. It is just as impossible to reconcile the two ideas and make them win together as it was impossible for this government to maintain itself any longer under the old discordant regime of freedom and slavery.” True temperance, she maintained, was a matter of personal moral responsibility. In her 1914 address before a Progressive Party luncheon in Portland, she argued:

“Oh” somebody says, “doesn’t God prohibit everything that is evil? Aren’t the Ten Commandments full of prohibition?” Yes, the Ten Commandments say, “Thou shalt not steal,” but the Ten [C]ommandments do not hide away in the bowels of the earth everything that man can steal. On the contrary, the Ten Commandments place in your way and mine temptation and say to us, “Resist it or take the consequences.” . . . We can never have temperance in its truest sense until we have raised men and women who are willing to abide by the rule of self- protection.

Only by successfully surmounting temptation could this morality be perfected, a process which the law would short-circuit. Her 1909 O.S.E.S.A. address continued:

Don’t imagine that you can ever make laws to govern men. All you can do through the law of liberty, is to so elevate the standard of morality, through expanding opportunities for yourselves, that men will strive instinctively to meet, from within their own consciousnesses, the highest laws that are innate within even the lowliest and most depraved man or woman, and only await the soul of development under the laws of liberty and responsibility.

Moreover, she believed, prohibition would doom suffrage by arousing the organized opposition not only of the liquor industry but of secondary trades from farmers to coopers and barrel-makers. In “Ballots and Bullets” (1889), her most famous speech on the topic, she warned: “Whenever our demand for our right to vote is based upon an alleged purpose to take away from men any degree of what they deem their liberties, or own right of choice we simply throw boomerangs that recoil upon our own heads.”

Scott Duniway vigorously defended these views at every opportunity. Her 1914 autobiography, Path Breaking, is largely an apologia for this position.57 But her polemics antagonized W.C.T.U.ers and suffragists who believed that those mobilized by prohibition would support woman’s rights as well. As a result, Scott Duniway endured repeated and often vicious charges that she had sold out to the liquor interests, and efforts, both overt and covert, to subvert her leadership.

Scott Duniway relied on arguments from principle in response to her understanding of women’s rhetorical situation. Even the casual observer of contemporary red state-blue state politics knows that deliberation, which implicates differing views of the public good, is inherently contentious and may be extraordinarily divisive. Even predicting the consequences of a proposed action is risky business, and invites disagreement among those whose tolerance for uncertainty differs.58 In this contentious context, appeals to shared principles tend to transcend disagreement and unify members of the body politic: Advocates may (and did) vigorously contest the expediency of woman suffrage, but who can dispute the desirability of freedom? Moreover, principles possess a moral legitimacy typically absent from arguments about the practical consequences of an action. Abigail believed that men would find it more difficult to oppose woman’s rights claimed according to the same principles by which they claimed their own.59

Nonetheless, Scott Duniway was not simply a starry-eyed theorist; she predicted, and hoped, that votes for women would have consequences. These consequences, however, would come not from the particular votes that women would cast, but from the human moral progress that equal suffrage would signify and advance. Thus, temperance will result, but not because women vote for prohibition. Similarly, equal suffrage will lead to financial independence and stability for both sexes because women’s improved status will call forth a heightened moral sense in men: “When women become voters . . . they will have taken the first step to become lawmakers. And when they are lawmakers, their equality in property rights will follow as a natural sequence. Then . . . men will delight in reforming themselves voluntarily, that they may be considered worthy of the love and honor that free, enlightened, independent womanhood can alone bestow.”60

Scott Duniway employed expediency arguments occasionally, when she judged that they would not be controversial. She also was keenly aware of the importance of appeals to expediency in another way: She sought to counter adverse appeals, especially assertions that suffrage would undermine the home. To the standard charges that suffragists were man-haters and home-wreckers, she responded in several ways. While the interests of men and women differed, she insisted, they were always interdependent and complementary. She often compared unequal relations between the sexes to dislocated shears that could not function effectively; suffrage would make these relations more, not less, harmonious.61 In “Woman in Oregon History” (1899), commemorating the fortieth anniversary of Oregon statehood, she declared: “The interests of the sexes can never be identically the same; but they are always mutual, always interdependent, and every effort to separate them results, primarily, in discontent and ultimately in failure.” She stressed that most women were not man-haters, but in fact liked men a good deal better than they liked each other, and she roundly criticized the “sour-souled, vinegar-visaged” exceptions to this rule, whom she recommended “steal away and die.” Often with a healthy dose of sarcasm, she cited the experience of those states in which woman suffrage had been approved to disprove the “theoretical” claims of the doomsayers. During the 1906 campaign, replying to a local politician’s claim that suffrage would “turn women into men,” she mocked:

Look at Wyoming: There hasn’t been a woman within her borders since 1869; no man has had a button on his shirt or a baby in his house for 35 years. Look at Colorado: Not a woman in the state; no man in that woman-forsaken land has had a darn in the heel or toe of his sock for 13 awful years. Look at Idaho: Not a woman to be seen. Look at Utah: Polygamy is doomed.62

Similarly, she proudly held up her successful children as further refutation of the claim that suffragists would destroy motherhood. During a Woman’s Congress in Portland in the summer of 1896, for example, she followed Hubert at the podium and quipped: “Dear friends, it is not necessary for me to tell you that this is one of my poor, neglected babies. People have said that Mrs. Duniway is traveling around the country and leaving her children to grow up in drunkenness, viciousness, idleness, and no one knows what, and here you see the result.”63

Finally, Scott Duniway loved to turn the tables. For instance, in reply to the charge that equal rights would cause women to abandon home and family, she conceded women’s maternal instinct and domestic inclination, arguing that these were so powerful that equal rights could not entice women to abandon them: “We have no fear of becoming the determined enemy of man. We do not believe that woman can educate herself out of herself, that she can lose her femininity by intellectual or business pursuits or eradicate the emotional side of her nature.”64 Once, when asked whether she would be willing to join the armed forces if allowed to vote, she noted that the questioner was no longer a soldier and had never been a sailor, retorting: “Then, sir, since, by your theory, nobody ought to vote unless they fight, and you are not now a fighter, ought you not to be disenfranchised along with the women?”65

Although many of these basic arguments were not original, they illustrate three important points. First, Scott Duniway preferred the least divisive of deliberative appeals, reassuring often hostile audiences by arguing from generally accepted principles of liberty and muting her challenge to premises about woman’s sphere. Second, she was well-versed in the repertoire of arguments both for and against equal rights. Third, she possessed a keen analytical mind and was a highly capable arguer.66

Epideictic

The most distinctive, noteworthy aspect of Abigail’s public address, however, is that it often eschewed deliberative speaking in favor of a kind of oratory called epideictic. This genre encompassed several prominent speech forms in the ancient world, including eulogies for Athenians who had died in battle (of which Pericles’ funeral oration is the most famous surviving example), celebratory speeches at festivals (e.g., at the Olympic Games), and addresses recounting a person’s deeds and achievements (such as Gorgias’ and Isocrates’ famous discourses on Helen of Troy).67 Such speeches often are called ceremonial or occasional because they tended to occur on certain, even recurrent, occasions of public importance; Fourth of July celebrations and Presidential inaugurations would be modern examples. As Scott Duniway’s speeches illustrate, however, they could be given under other circumstances as well.

Epideictic addresses are marked more surely by other characteristics. First, they are speeches of praise or blame, usually of a person (fallen warriors, great athletes, the [in]famous) or persons (our forebears, the American nation). Second, epideictic is derived from epideixis, the Greek word for exhibition or display, which suggests a kind of performance. Such addresses tend to draw attention to the speaker whose rhetorical abilities are on display for all to see and judge. For this and other reasons, these speeches are oriented primarily toward the present. Third, and most importantly, an epideictic performance is judged according to the speaker’s skill in associating (in speeches of praise) or dissociating (in speeches of blame) her subject with cultural truths that are universally (or nearly so) accepted, such as: to give one’s life for one’s country is noble and heroic; extraordinary feats are more admirable than ordinary ones; Americans are God’s chosen people; and so on. Because their truths are so widely accepted as cultural “taken-for-granteds,” epideictic speeches unify audiences by articulating their commonalities, rather than dividing them, as deliberative addresses often do.

Yet, it is not quite this simple. Aristotle noted that epideictic and deliberative addresses are related because to praise is in some respects akin to urging a course of action: “The suggestions which would be made in the latter case become encomiums when differently expressed.”68 To praise the President’s character is implicitly to endorse his policies; conversely, to denounce the man is implicitly to reject that for which he stands. Scott Duniway’s public advocacy splendidly and vividly illustrates the way in which both flattery and censure can be made to serve deliberative ends by indirection.

Scott Duniway lavished praise on the men of the Pacific Northwest, particularly the deeds of pioneer men in clearing and settling the land, their independent spirit and love of liberty, and their sense of fairness. Similarly, she praised the region’s women, particularly their strength and courage in enduring pioneer hardships at least as great as those faced by men, their endless domestic toil, and their accomplishments in business and the professions.69 In “A Pioneer Incident” (1902), she claimed: “The men and women who first take up their line of march across untracked continents, who settle upon the outposts of civilization and raise the standard of Liberty for all the people to higher planes are the very best and most enterprising citizens of any land.” Her address at the Lewis and Clark Exposition (1905) appealed to “the broad-brained, big-hearted men of this mighty State, in the midst of whose splendid achievements we are so proudly standing . . . to arise in the majesty of your patriotism and chivalry and swing wide the doors to our joint inheritance. . . .”70

Praise of women’s exploits in particular “demonstrated” that women had earned equal rights.71 “Success in Sight” (1900) contains Scott Duniway’s most explicit expression of this theme:

Nowhere else upon this planet are the inalienable rights of women as much appreciated as on the newly settled borders of the United States. Men have had opportunities in our remote countries to see the worth of the civilized woman who came with them or among them to new settlements after the Indian woman’s day. And they have seen her, not as the parasitic woman who inherits wealth, or the equally selfish woman who lives in idleness upon her husband’s toil, but as their helpmate, companion, counselor and fellow homemaker. . . .

Whether celebrating men or women, flesh-and-blood persons or somewhat mythic frontier personae, such praise invited audiences to live up to these models of humanity, to become them.72

Scott Duniway’s own persona also contributed to the epideictic mode. Her speeches often were partly autobiographical, recounting her experiences as a mother of six, a pioneer settler of Oregon and a path breaker in the movement for equal rights.73 The former typically dwelt on the unceasing toil and drudgery that were the lot of a frontier wife, while the latter emphasized her decades-long, herculean, sometimes solitary, and often ill-appreciated labors, at great personal sacrifice, for the cause. As she grew older, Abigail often attributed her infirmities to overwork and expressed hope that she would live to see her life’s work consummated. On the brink of the (finally successful) 1912 referendum, she pleaded:

I am an old woman now. The hand that pens these lines is rheumatic and feeble. The present equal suffrage campaign, launched by myself, is offered as a loving appeal to the present voters of Oregon for the enfranchisement of your mothers, wives and sisters. . . . I do not, myself, expect ever to be able to cast a full free ballot, but I do hope that you gentlemen, who have never been compelled to struggle for the right to vote, will vote 300 X Yes and send me to heaven as a free angel.74

Such pleas may be self-aggrandizing plays upon cheap emotionalism, appeals to respect for maternity, shame, and guilt.75 But they also should be considered in their larger epideictic context. In praising herself she praises the women of the Pacific Northwest whose virtues and experiences she shares and comes synecdochically to represent. They all are “path breakers” in this dual sense, pioneers of the Pacific Northwest and for equal rights, and Scott Duniway’s life comes to stand for Everywoman’s. If her life demonstrates that she has earned equal rights, she enacts her larger epideictic “claim” that women deserve the ballot.

Even more than deliberative arguments from principle, epideictic advances Scott Duniway’s persuasive objectives. Praise ingratiates and does not threaten.76 Unlike deliberative address, epideictic’s focus on the present reduces a speaker’s need to detail a future with uncertain attraction for audiences. Moreover, just as appeals to principle deemphasize consideration of the pragmatic desirability of policies, epideictic emphasizes character, not courses of action. Scott Duniway’s characterization of temperance as a moral, rather than legal, matter and her praise of the pioneer’s rugged individualism are mutually reinforcing: Both emphasize personal responsibility without specifying precisely what responsible action must entail. Hence, rather than challenging audience beliefs about right and wrong actions, Scott Duniway invites audiences to become certain kinds of people, those who live according to certain accepted principles, presupposing that people of right character will do the right thing.

The danger of epideictic, however, is that, although praise assuages, blame estranges. Herein lies the great irony of Scott Duniway’s signature strategy, given her understanding of women’s rhetorical situation. Generous with flattery expressed in the high style, Scott Duniway also was liberal with censure couched in the low style. Sharp-witted and sharp-tongued, she could excoriate an opponent as quickly as laud an ally. Reportedly, her extemporaneous stump speeches were laced with prickly humor. Her more formal addresses were comparatively circumspect. In them, she invariably praised the support for suffrage shown by “all the best classes” of men, but scornfully condemned the opposition of the “vicious” classes, particularly immigrants. At a reunion of the Oregon Pioneer Association (1882), she appealed to the patriotic and chivalrous instincts of the former for protection from the latter:

We are not afraid of the votes of wise men, moral men, intelligent, liberty-loving, progressive men; but we know, alas! that every ignorant, vicious, drunken, law-breaking or tyrannical man has a vote which counts at the polls as surely as the vote of a thinker, statesman and philanthropist. Women cannot reach the prejudiced, ignorant and vicious voting elements to educate and enlighten them. Such men consider themselves superior to those Oregon pioneers–these wives and mothers of orderly and law-abiding citizens–and we must look to the leading men of the State, like those around me, for protection from the proscriptive ballots of the lawless, ignorant and wicked hordes who presume to dictate our destiny.

Here, in a typical move, the appeals to chivalry and to suffrage as recompense combine with concerns over immigration to argue that woman suffrage would strengthen the “home element” against the less virtuous classes. Scott Duniway was fond of condemning the injustice that placed the “wives and mothers” of “self-respecting men” in the same political category with “idiots, insane persons, criminals, Chinamen not native-born and Indians not taxed.”77 In this way, flattery and guilt are accompanied by fear.

Scott Duniway was equally impatient with “dolls”–-those wealthy, privileged women who, with others to perform their labor, felt no need for equal rights–-and with the “one-idead” and “man-haters” among suffragists. But her disagreements with others were not only philosophical. She frequently came into heated conflict over political tactics as well. Scott Duniway cautioned against what she called “hurrah campaigns,” run by workers “imported” from the eastern states, which, with very public press coverage, rallies, and demonstrations, brought much attention to the cause. Such publicity, Scott Duniway believed, was counterproductive, arousing also the organized opposition. These campaigns, she contended, invariably failed. Instead, Scott Duniway favored the “still hunt” method which sought, through (not coincidentally, her) letter-writing and personal lobbying, to win the quiet support of key officials, respected organizations and leading men of the state.78

In her most conciliatory moments, Scott Duniway’s approach to those with whom she disagreed was to admonish and correct, not to assail and humiliate. In “Ballots and Bullets” (1889) she concluded: “If in anything I have said tonight I have given any one of my sincere co-workers a moment’s pain, I can only say I am sorry, but I must not withhold the facts.” Defending her views on prohibition in 1886, she wrote:

We do not say these things in a spirit of faultfinding or dictation. It pains us inexpressibly to thus proclaim the truth and arouse your hostility. But it is the truth, and we hereby tell it in love and kindliness, not seeking or expecting personal reward, but braving even your own condemnation if haply we can humbly help to make you free indeed.79

But Scott Duniway’s capacity for vituperation is also evident in her newspaper columns and letters, which often engaged in the name-calling, witty sarcasm and bitter vitriol characteristic of the “Oregon-style journalism” of her day.80 She lambasted Supreme Court Justice Ward Hunt, who rejected the Fourteenth Amendment defense in Anthony’s 1873 illegal voting trial, as “an angular brained, one idead old fossil, who would excel as a first class donkey.”81 When Horace Greeley refused to endorse woman suffrage, she called him “an infinitesimal political pigmy of reality” and “a coarse, bigoted, narrow-minded old dotard.”82 She exchanged fire with opposition editors, nicknaming one prohibition paper the “Temperance Turkey Buzzard” and denouncing its editor as “a noisy simpleton.”83 When another slandered the “new woman” as “the most ridiculous production of modern times” and “the most ghastly failure of the century,” and concluded that “[s]he will certainly fail to become a man, but she may succeed in ceasing to be a woman,” Abigail’s retort was withering. Pointing out the editor’s “addle pated condition,” she blasted: “Max O’Rell needn’t worry. There isn’t the least danger that he will ever be either a man or a woman; and, there being no present or prospective mate for the nondescript he has succeeded in making of himself, (the new woman as he sees her being a myth) there is little danger that his ilk will multiply.”84 In the vilification arena, Scott Duniway clearly could hold her own.

This habit of personalizing disagreement unquestionably generated intense hostility, transforming potential allies into bitter adversaries. Scott Duniway alienated many regional and national suffrage leaders. In 1895, Carrie Lane Chapman Catt confided to Emma Smith DeVoe of Illinois, “I now believe that Mrs. Duniway is a jealous-minded and dangerous woman.”85 Abigail was ordered to remove herself from the decisive 1896 campaign in Idaho; the National American Woman Suffrage Association (N.A.W.S.A.) sent Smith DeVoe and Laura M. Johns of Kansas to spearhead the effort, and Chapman Catt spent a month campaigning and strategizing in 1896.86 Afterward, Scott Duniway was unapologetic: She felt denied proper credit for her role in the victory and continued her vigorous attack on eastern methods.87 But even her old mentor, Anthony, admitted to Bewick Colby that Abigail’s head was “so full of crochets that it is impossible for her to co-operate with anybody.”88 Thereafter, Scott Duniway confined her work chiefly to Oregon. She directed the still hunt campaign of 1900, which failed by less than two thousand votes. But her resentment of eastern “interference” boiled over in the aftermath of the N.A.W.S.A.-directed campaign of 1905-06, which failed by over ten thousand votes. Scott Duniway termed the effort “disastrous” and interpreted the result as an exoneration of her own methods and a repudiation of the National’s leadership.89 Abigail, who thought the Reverend Anna Howard Shaw (whom she sometimes called “Anner Pshaw”) a powerful platform orator but an exceedingly poor organizer, accused the N.A.W.S.A. President of malfeasance in office and threatened to have her arrested, should she set foot in “Duniway territory” again.90 Shortly after this setback, she beat back a prohibitionist attempt involving Bewick Colby, publisher of the Woman’s Tribune, to seize control of O.S.E.S.A. And her subsequent appeal to N.A.W.S.A. for seed money with which to launch a new effort, unsurprisingly, was rebuffed; the National, she was told, had concluded that “the only thing that could be done for Oregon was ‘to leave her severely alone.[‘]”91

Scott Duniway was not always gracious even when she could afford to be. Years after the 1906 defeat, even after suffrage had come to all three Pacific Northwest states, she used the occasion of Shaw’s refusal to pay income taxes to reopen old wounds, commenting:

It has been my experience that it has been better to obey the laws until we get the chance to amend them. If we had pursued the tactics of Dr. Shaw in the Northwest, we should never have had equal suffrage in Washington, Idaho or Oregon. I consider our victory here in Oregon, after the 42 years of my work, a repudiation of Anna Shaw’s method.92

In 1914, when a member of the W.C.T.U., in polite disagreement, returned the copy of the polemical Path Breaking that Scott Duniway had sent her, the latter shot back:

You are not the only woman who owes her enfranchisement to my humble efforts who has proved ungrateful. But you and – you know who – are the only ones who have capped the climax by refusing to accept my little History that will live and flourish long after you are both forgotten. And thou too, Brutus?93

Clearly, Scott Duniway was opinionated, often strident, even vain. Unquestionably, magnified by epideictic’s general tendency to draw attention to the speaker, such outbursts often made Scott Duniway herself, not the gospel of woman’s rights, the issue. Yet, by defining repellant characters, her vilification of opponents magnified the contrast between noble and ignoble personae, rendering more stark and compelling the choice between characters which she presented to audiences. Because blame is but the counterpart of praise, her outbursts, while impolitic, were understandable.

Men and women were not the only objects of Scott Duniway’s adulation. She reserved her most lyrical and effusive praise, expressed in both verse and prose, for the “paradise” that was the Pacific Northwest. At virtually every opportunity, she lauded its magnificent scenery, abundant natural resources, temperate climate, space for settlement and prospects for commerce.

At first blush, these encomia to nature seem little more than standard, provincial boosterism (which they certainly were).94 But, in fact, they also play a vital role in Scott Duniway’s larger epideictic efforts by literally grounding the cause of equal rights in a place. Moreover, because the place itself is unique, this cause becomes its special destiny. In “Woman in Oregon History” (1899) she contended: “All great uprisings of the race, looking to the establishment of a larger liberty for all the people, have first been generated in new countries, where plastic conditions adapt themselves to larger growth.” Scott Duniway often argued that the West in general, and the Pacific Northwest in particular, was the most fertile of grounds, in which the cause of equal rights could and would take deepest and firmest root. In addressing the Oregon Pioneer Association in 1882, she sounded the theme she was to echo before the N.A.W.S.A. convention in 1899 (in “How to Win the Ballot”):

There are lessons of liberty in the rock-ribbed mountains that pierce our blue horizon with their snow-crowned heads and laugh to scorn the warring elements of the earth and air; lessons of freedom in the broad prairies that roll away into illimitable distances; in the gigantic forests that rear their hydra heads to the very zenith and touch the horizon with extended arms; lessons of truth, equality and justice in the very air we breathe, and lessons of irresistible progress in the mighty waters that surge with irresistible power through the overshadowing bluffs where rolls the Oregon.95

It is not strange that noble men living in such a country should have early learned to preach and practice the grand gospel of equal rights.

According to rhetorical theorist Kenneth Burke’s principles of dramatism, this strategy features the scene, and “logically” calls forth suitable acts and agents in keeping with this scene.96 In Scott Duniway’s case, the land is free, just, and irresistible, and has called forth a pioneer people imbued with the spirit of liberty; here we see what Burke calls the “scene-agent ratio” at work.97 It remains for this people to consummate the act that is consistent with this scene, that is, to free women by granting suffrage. Yet, by the logic of the “scene-act ratio,” because the scene is free and just, the acts contained by this scene will partake of these qualities.98 Further, the scene itself is described as irresistible. Hence, suffrage’s victory is inevitable. The region demands, and will result of necessity in, a civilization founded on principles of equality between the sexes. It is, in a word, destiny.

Variations on this central theme of irresistible progress, which was common in much nineteenth-century American public address, are common in Scott Duniway’s rhetoric as well. A firm believer in human improvement, she often marveled at advances in science and technology that were transforming labor both in and outside the home, and commented frequently on the evolving state of spiritual awareness. The advance of woman’s rights was for her a natural, ineluctable part of human socio-political development. “The world is moving,” she was fond of saying, “and women are moving with it.” Even in the face of defeat after defeat, she unswervingly heralded the inevitable triumph of her cause. Her 1884 address to the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Woman Suffrage poses the rhetorical question: “Gentlemen of the committee: Do you think it possible that an agitation like this can go on and on forever without a victory?” Twelve years later, she was still prophesying that “equal suffrage is marching toward victory just as surely as the light which leaves the sun and travels toward the earth will reach the human eye.”99

This scenic emphasis accomplishes four important persuasive objectives. First, it mitigates the temporal and pragmatic limitations of epideictic appeals grounded in arguments from principle. No longer restricted to abstractions adhered to in the present, Scott Duniway can envision the future of a place, predicting the amelioration of drunkenness, divorce, prostitution, crime, political corruption, war, labor unrest, and myriad other social ills.

Second, a scenic emphasis reinforces the contrast between noble and vicious characters, between which audiences are asked to choose, with a complementary (and equally unequal) choice between alternative futures of progress and regress. Indeed, because inevitable progress is a feature of the scene, there really is no choice at all: The audiences of the Pacific Northwest must become what the land requires.

Third, the momentum generated by the scene can evoke optimism in those who favor its direction and pessimism in those it threatens to leave behind. In many of Scott Duniway’s addresses, notably in “Upward Steps in a Third of a Century” (1906), ever-increasing support for the cause of woman’s rights is part of humanity’s broader advance. Her speeches thus offer hope to woman’s rights advocates while resigning opponents to defeat.

Fourth, by locating the future in the inexorable unfolding scene itself, she deflects responsibility from woman’s rights advocates, insulating the woman’s rights movement from the criticisms of those who would oppose and obstruct this future. Even her own rhetorical insensitivity is excused, at least partially; in her plain speaking, she often averred, she intended no “personal” offense, but sought only to speak the “truth.” In so doing, she simply gives voice to the scene. What the land has set in motion no woman is to blame for and no man may stop; it is destiny.

These deliberative and epideictic strategies span Scott Duniway’s entire public career. As time passed and Oregon became more settled, the original pioneer experience more remote, she strove to maintain the salience of her message by recreating this experience in historical narrative.100 Often she would be a prominent character herself; at other times she would recount the exploits of others. In both cases, she sought to keep alive not simply the memory of an era but that era itself, inviting audiences to become pioneers and, hence, precisely the kind of audiences to whom her discourse would appeal.101

Conclusion

In sum, Abigail Scott Duniway was a controversial advocate whose rhetoric, adapted to frontier conditions, could inspire as well as infuriate. Her combativeness and insistence upon running campaigns in her own way arguably slowed the progress of the equal rights movement in the Pacific Northwest by alienating potential allies both within and without the movement.102 Yet, her prodigious pen and outspoken voice, her indefatigable determination, and ultimately her stature as a public woman were unmatched in the region. The triumph of equal suffrage in the Pacific Northwest was in large measure her personal triumph as well. Admittedly, she played a larger role in Washington Territory’s brief experiment with suffrage in 1883 than in subsequent campaigns and, as noted above, she was removed from the decisive drive in Idaho. Nonetheless, her early efforts laid the groundwork for extensions of suffrage in Idaho in 1896 and Washington in 1910. After five unsuccessful campaigns that had begun in 1884, the voters of Oregon finally extended the franchise in 1912. On November 30, 78-year-old Abigail Scott Duniway penned and countersigned the gubernatorial proclamation that made votes for women a reality.

Victory was a watershed, but not the end. In December, 1912, Abigail became the first woman summoned for jury service in Oregon. On February 14, 1913, she became the first registered female voter in Multnomah County.103 At a voter registration rally a few days later, she spoke on “The Voter’s First Duty,” and cast her first vote at the municipal election later that year.104 In 1914, she continued her campaign against prohibition and completed her autobiography. That September, at her home, a new women’s group was organized for the purpose of improving election processes, including vote tabulation and reporting, and promoting Republican candidates for office.105 In 1915, “that dear old Mrs. Duniway” traveled all the way to the San Francisco world’s fair, delivering “one of the most important and thrilling” speeches at the suffrage booth at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition.106 But the end was nigh. On October 2, 1915, surgery was performed at Good Samaritan Hospital on a gangrenous toe that Abigail–-stubbornly independent in all things–-had tried to treat herself. An initially “favorable” prognosis soon became a one-in-a-thousand chance and, on October 11–shortly before her eighty-first birthday–the acknowledged “mother of woman suffrage in the Pacific Northwest” died, never to see passage of the Nineteenth Amendment.107 Fittingly, “her feet gave way before her heart.”108 Nine days later, the Morning Oregonian reported what she had left behind:

The late Abigail Scott Duniway left an estate valued at $600. That is not all she left, however. She left a family of sturdy sons who are a credit to the citizenship of Oregon. She left the memory of life-long endeavor in overcoming obstacles to serve as stimulus to those who would weary in well doing when they know they are in the right. She left an example to the womanhood and motherhood of the Northwest to show they can rise above the common, sordid life and become units of progress in the commonwealth without sacrifice of home ties and the holier instinct. The money value left by Mrs. Duniway is insignificant and the least.109

-

- This is a revised and expanded version of

Lake, “Abigail Scott Duniway.”

- Reproduced with permission of ABC-CLIO, LLC.

NOTES

- Both sides of Abigail’s family came to Illinois from Kentucky. Her paternal grandparents, James and Frances Tucker Scott, had come to Plum Grove in 1825, where he quickly assumed constabulary duties. In 1827, they became the first settlers in Groveland Township, building a cabin in the timber in the southeastern corner of section 35. That year, James was appointed to the first Circuit Court grand jury; by 1829 he was a deputy sheriff and, from 1832 to 1835, he was sheriff. Meanwhile, Frances welcomed newcomers with a gift of a hen and chicks ( History of Tazewell County 207, 231, 240, 475, 563, 713). Her maternal grandparents, Lawrence and Mary Smith Roelofson, came first to White County, c. 1821, and then to Groveland Township in 1834, the year in which Abigail was born ( History of Tazewell County 508). [↩]

- (1811-1852): born near Henderson, Kentucky; eighth of twelve children, including nine girls, of Mary Smith and Lawrence Roelofson; family came to Illinois, c. 1821; met John Tucker Scott while assisting sister Esther Roelofson Johnson (wife of Rev. Neill Johnson, minister and missionary of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church) with childbirth on neighboring farm; difficult childbirths left her semi-invalid; did not want to go to Oregon but, following loss of twelfth child at birth, Tucker Scott believed that improved climate might cure her; died of “plains cholera” on Platte River, thirty miles west of Fort Laramie, during overland trip; “For the gentler sort of womankind–and to this type by all accounts Ann Roelofson belonged–life in the wilderness was a long agony of self-sacrifice” (Moynihan, Rebel 1-36, passim; Scott, History of the Oregon Country 1: 10). [↩]

- (1809-1880): born Washington County, Kentucky, eighteen miles and six days from Abraham Lincoln’s birthplace and date; second of seven living children, including five girls, of Frances Tucker and James Scott, who married in 1806; family moved to Illinois, 1824, settling in Tazewell County, where he was postmaster and sawmill manager; married Ann Roelofson; lost farm, 1840, and went bankrupt, 1842; joined Sons of Temperance, 1842; with assistance of Edward Dickinson Baker, purchased first circular sawmill west of Ohio, 1846; major contributor, Groveland Cumberland Presbyterian Church; elected county road commissioner; removed to Oregon, 1852, becoming innkeeper of Oregon Temperance House, Lafayette; married Ruth Eckler Stevenson, 1853, whom he divorced for bearing another man’s child and then reconciled, settling with her at Scott’s Prairie, near Shelton, on Puget Sound, Washington Territory, 1854; returned to Clackamas County, Oregon, near the Duniways, 1857; moved to Forest Grove, 1865; successful farmer, sawmill operator; benefactor, Pacific University (Moynihan, Rebel 1-50, passim; Scott, History of the Oregon Country 1: 132, 5: 217-19). [↩]

- James Lawrence (November 28, 1831-March 17, 1833); Mary Frances (May 19, 1833-September 9, 1930); Margaret Ann (October 27, 1836-September 24, 1865); Harvey Whitefield (February 1, 1838-August 7, 1910); Catherine Amanda (November 30, 1839-May 27, 1913); Harriet Louisa (March 9, 1841-January 2, 1930); John Henry (October 1, 1843-May 1, 1862); Edward Scott (March 13, 1845-April 10, 1845); Sarah Maria (April 22, 1847-November 24, 1901); William Neill (December 4, 1848-August 27, 1852); Alice (September 8, 1851-September 8, 1851). [↩]

- As her family called her; in adulthood, Abigail disapproved of such pet names (“Names and Naming”). [↩]

- Those passing Fort Kearney on the Platte River (the main route) as of July 14 (estimated as two-thirds that for the year) were said to include 18,765 men; 4,270 women; 5,590 children; 7,793 horses; 4,993 mules; 74,783 cattle; 7,516 wagons; 23,980 sheep; 1 hog. Four people passed with wheelbarrows, several with handcarts, and others with backpacks. Numbered among these was a long train comprising the eleven members of the Scott party, in five wagons, and seventeen other adults in twenty-two more wagons. (The Scotts had departed Groveland on April 2; the train reached Fort Kearney on May 29.) The Scotts would lose nearly half of their forty-five cattle, and two horses, over the course of their six-month journey (Scott, History of the Oregon Country 3: 226, 232-33). [↩]

- Esther Roelofson and Rev. Neill Johnson, Abigail’s aunt and uncle, had come to Oregon from Iowa the year before (Garces). [↩]

- Benjamin Charles Duniway (1830-1896): born Pike County, Illinois; came to Oregon, 1850; took up donation land claim east of Woodburn, south of Oregon City; married Abigail Jane Scott, August 2, 1853; bought farm in Yamhill County, 1858; sold farm to cover debts, moving to Lafayette, 1862; serious teamster accident rendered him semi-invalid; moved to Albany, 1865, and to Portland, 1870 (Scott, History of the Oregon Country 3: 248). [↩]

- Moynihan, Rebel 75. [↩]

- “San Francisco County Woman Suffrage Association.” [↩]

- Larson, “Washington” 51. [↩]

- On February 14-15, at Oro Fino Hall in Portland (Oregonian 15 Feb. 1873; New Northwest 29 Jan. 1875). Clark says that Scott Duniway participated in its organization but was not an officer in the new O.S.W.S.A. (History 712). [↩]

- The definitive biography is Ruth Barnes Moynihan’s doctoral dissertation, “Abigail Scott Duniway of Oregon: Woman and Suffragist of the American Frontier,” revised and condensed as Rebel for Rights: Abigail Scott Duniway. Other valuable scholarly studies include Letitia Lee Capell’s master’s thesis, “A Biography of Abigail Scott Duniway”, Martha Frances Montague’s master’s thesis, “The Woman Suffrage Movement in Oregon”, and Leslie McKay Roberts’ bachelor’s thesis, “Suffragist of the New West: Abigail Scott Duniway and the Development of the Oregon Woman Suffrage Movement”. An engaging but less informative popular history is Helen Krebs Smith, The Presumptuous Dreamers: A Sociological History of the Life and Times of Abigail Scott Duniway (1834-1915). Among the best shorter accounts are L. C. Johnson’s entry in Notable American Women, 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary, Moynihan’s “Abigail Scott Duniway: Mother of Woman Suffrage in the Pacific Northwest,” and Linda Steiner’s “The New Northwest.” Jane Kirkpatrick’s Something Worth Doing is a fictionalized account of Abigail’s life that rings true. [↩]

- Degler; Endres, “Forerunner.” [↩]

- See Ward, “Emergence”; Edwards, Sowing; A. Duniway, “Susan B. Anthony’s Visit.” Laura de Force Gordon and Dr. Carrie F. Young (a temperance advocate), both of California, also lectured in Oregon that year, leading Clark to comment: “This first year of active campaigning had more lecturers in the field than any subsequent year until the campaign of 1907” (History 709). Three years later, Young attacked Scott Duniway’s spiritualist interests as un-Christian, provoking a scornful reply in which Abigail called her “a peripatetic lecturer upon any side of any subject for which she thinks people will drop the most coin in her hat,” and the charge “superabundant bile.” [↩]

- Concerning her work in Oregon and Washington, see Myres 336 [n. 42]. Regarding her efforts in Idaho, see Larson, “Woman’s Rights” 4; Abigail Scott Duniway, letter to Mrs. M. C. Athey, 6 Jan. 1897, in Scrapbook #2, Abigail Scott Duniway Papers. Her 1886 description of activities appears in New Northwest 7 Oct. 1886. [↩]

- She went by train from San Francisco to New York in 1872, by stagecoach from Walla Walla in 1876 and 1880, and by Pullman car on the newly completed railroad from Portland to Washington, D.C., in 1884 and 1885. Sometimes she received free passes, often arranged by her brother, Harvey, but mostly she paid for trips by lecturing along the way (Moynihan, Rebel 14). Her grandson recalled: “In 1876 she talked her way across the continent to the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia” (D. Duniway, “Abigail Scott Duniway” 204). Abigail was away from home frequently and for extended periods. In that centennial year of 1876, for example, she was elected a vice-president of the National Woman Suffrage Association in New York in May; was signatory to the “Declaration of Rights for Women” that N.W.S.A. delivered to the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia on July 4; attended the American Woman Suffrage Association convention, also in Philadelphia, and the National Woman’s Christian Temperance Union convention, in Newark, New Jersey, in October, and the Illinois Woman Suffrage Association in December (History of Woman Suffrage 3: 319, 3: 34, 2: 850; infra n. 16; Ballot Box Jan. 1877). Her 1880 trip included, in June, a mass meeting in Chicago, called by N.W.S.A. for the purpose of lobbying the Republican national convention (History of Woman Suffrage 3: 176). In March, 1884, following the N.W.S.A. convention in Washington, D.C., she participated in conventions of the New York and Connecticut state societies, and spoke before the judiciary committee of the New York state legislature (History of Woman Suffrage 3: 334, 437). In 1885, she attended the N.W.S.A. convention, in Washington, D.C., in June and the A.W.S.A. convention, in Minneapolis, in October (History of Woman Suffrage 4: 414). By comparison, her 1909 trip to Seattle for the N.A.W.S.A. convention was a puddle-jump, even for a rheumatic 74-year-old (History of Woman Suffrage 5: 254). Willard and Livermore claim, with considerable justice: “While advocating woman suffrage she has undoubtedly traveled more miles by stage, rail, river and wagon, made more public speeches, endured more hardships, persecution and ridicule, and scored more victories than any of her distinguished contemporaries of the East and middle West” (“Duniway, Mrs. Abigail Scott” 264). [↩]

- In 1876, Scott Duniway traveled all the way to Newark, New Jersey, to attend the National Woman’s Christian Temperance Union convention, at which she was elected vice-president for Oregon; in 1883 she was president of the state W.C.T.U, although she did not attend the national convention, in Detroit (National Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, Third 105; National Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, Tenth 118).

Although her teetotaling convictions were genuine, Scott Abigail’s foray into temperance was rocky from the outset–-and went downhill from there. Although many churches caught temperance fever in the mid-1870s, they usually remained hostile to the gospel of freedom. Abigail joined a temperance society that met at a Taylor Street church. When she would try to interject a few good words for suffrage, its pastor would cut her off. One night when she rose to speak, the minister raised his hand, a signal for the congregation to sing. Each time they finished, she would try again and they would drown her out again, until the minister closed the meeting by leading everyone in the Doxology. At the next meeting, Abigail sat in the front pew, biding her time. At a lull in the proceedings, she jumped up and cried, “Let us pray!” For twenty minutes, she petitioned the Almighty: “She prayed that every yoke might be broken and the oppressed go free; that the ‘mother sex’ might be freed from servitude without wages; that press, public, and pulpit be led to realize that political freedom for women could no longer be denied . . . [and] that society be freed from the bigotry and tyranny of the pulpit as well as from the vice and tyranny of the saloon.” The instant she said “Amen,” the minister called for the Doxology (Richey, “Unsinkable” 87). When her opposition to prohibition solidified, Abigail became a pariah in temperance circles. [↩]

- Scott Duniway’s experience with woman’s clubs was roughly the reverse: Initially skeptical, she came to embrace, and be embraced by, them. At first, she believed them to be the idle diversions of leisured women; see “Oregon State Woman Suffrage Association.” In the mid-1890s, however, her eyes were opened (in her account, by Abigail Howard Hunt Stuart of Olympia, President of the Washington Woman’s Club) to their potential as a means of reaching more conservative women (see A. Duniway, Path Breaking 209-17; “Greeting and Reminiscence“). Abigail helped found the Portland Woman’s Club in 1895. In 1897 she led monthly parliamentary law drills, teaching “the forms of public business,” and became president of the offshoot Women’s Parliamentary Law Club later that year. Early on, the P.W.C. supported–with reasonable success–free public libraries, public kindergartens, free school textbooks, a 5:00 closing law, and higher wages for teachers, and Abigail was elected president in 1902 (L. Roberts 137-38). Similarly, she was active in the Hindu-American Anti-Child Wife League “chiefly, because it opens the door to the equal rights movement among conservative elements which cannot otherwise be reached–as their sympathies are never enlisted in the sad cases that abound nearer home,” and was the League’s president in 1905 (Abigail Scott Duniway, letter to Clyde Augustus Duniway, 27 Mar. 1904, qtd. in L. Roberts 141). She also was second vice-president of the new Oregon Federation of Women’s Clubs (1899-1902), and its honorary president in 1911. Some claim that she was elected president in 1898 (L. Roberts 138; Bandow 17). Abigail’s club-related speeches in this volume include “Eminent Women I Have Met” (1900); “Presidents Past and Future” (1903); her 1905 address before the Oregon Federation of Women’s Clubs; and “Greeting and Reminiscence” (1913). On the woman’s club movement generally, see Blair, Clubwoman. [↩]

- Larson, “Washington” 51; Field 243. [↩]

- Woman’s Tribune 28 Oct. 1905. Others confirm this assessment. “As an extemporaneous speaker she is logical, sarcastic, witty, poetic and often eloquent. As a writer she is forceful and argumentative” (“Duniway, Mrs. Abigail Scott” 264). Governor Oswald West recalled: “She was a woman of ardent convictions, and possessed the courage and intellectual power to defend them” (248). [↩]

- According to Moynihan, she contributed to the “radical new Republican” Argus until 1860 and to the Oregon Farmer until 1862. Moynihan suggests that Abigail also wrote to the former under the pseudonym “Xenittie” and notes that she first wrote under her own name in 1859 (Rebel 13, 65-73). Another source, however, claims that she started a column, “The Farmer’s Wife,” for the Argus in 1860, continuing at least through 1865 (“Abigail Scott Duniway” 8). [↩]

- Argus 4 June 1859. [↩]

- Argus 23 Apr. 1859. [↩]

- The metaphor is her own (Path Breaking 26). Several experiences apparently contributed to her conversion. In 1860 she and a handful of women braved the ridicule of men to attend a campaign speech in Lafayette by Col. Edward Dickinson Baker (“Constitutional Liberty and the Aristocracy of Sex” n. 11), Lincoln’s law partner, a family friend from Illinois, and a friend of equal suffrage, who had come to Oregon and was running for the U.S. Senate. The 1862 bankruptcy that cost the Duniways their three-hundred-acre Yamhill County farm, and forced relocation to Lafayette, drove home to Abigail the consequences of women’s vulnerable status as legal nonpersons. This lesson was reinforced following the family’s subsequent move to Albany, three years hence, when, as proprietor of her millinery shop, Abigail witnessed the trials of wives forced to secret “butter and egg” money from profligate husbands in order to provide for their families. Later, she would assert that the lessons taught by this business venture “brought me before the world as an evangel of Equal Rights for Women” (Path Breaking 21; more generally, see Path Breaking 11-27; Moynihan, Rebel 62-83). [↩]

- Bennion, “Pioneer.” [↩]

- Steiner, “New Northwest.” Portions of the New Northwest have been republished in Ward and Maveety, “Yours for Liberty”: Selections from Abigail Scott Duniway’s Suffrage Newspaper and in Moynihan, Armitage, and Dichamp, So Much to Be Done: Women Settlers on the Mining and Ranching Frontier. The complete paper is now available via the Oregon Digital Newspaper Program, a project of the University of Oregon Libraries. [↩]

- A biographical sketch in the manifest for the Duniway/Scott Photograph Collection, Ph. 246, University of Oregon, indicates that she contributed to the Chicago Inter-Ocean and the Pacific Monthly “as well as some suffragist and local Portland papers.” [↩]

- Even Powers says only that it was listed as a Portland monthly in the Northwest Magazine for April, 1892 (719). Only one issue (December 2, 1891) evidently has survived. [↩]

- (1847-1916): born Graetz, Germany; accounts of early life differ; probably came to New York City, c. 1859, then to San Francisco/Sacramento, c. 1860; newsboy, errand-boy, advertising agent; attended night school; visited Portland, 1871; married Jennie Levy in Sacramento, December, 1871, returning to Portland to settle; published Portland city directory, 1873; publisher, West Shore, 1875-91; agent, Equitable Life Assurance Co., New York; founder and manager, Oregon Life Insurance Co. (forerunner, Standard Insurance Co.), 1905-16; rose fancier, contributor to Portland’s reputation as Rose City (Cleaver; cf. “Biography–Samuel, Leo (1847-1916),” Vertical File, OR Hist. Soc.; Lockley 2: 916-19). [↩]

- Described as “devoted to Literature, Science, Art, and the Resources of the Pacific Northwest,” it furnished an outlet for a number of early Oregon writers, including Ella Higginson, Joaquin (Cincinnatus Hiner) Miller, and Frances Auretta Fuller Barritt Victor (Lockley 2: 917; Turnbull 167-68; Corning 261). It also was a “booster” periodical that promoted immigration to the region (Mott 3: 57, 148). By one account, it enticed “hundreds” (Portland Evening Telegram 24 Aug. 1916); by another, “thousands and thousands” (Hodgkin and Galvin 187). No doubt, its wood cuts and zinc etchings–followed by lithographs in 1878, and color and tint-block illustrations in 1889 (Turnbull 167)–contributed to this success. Its boosterism undoubtedly appealed to Scott Duniway. Remarkably, even the most comprehensive history of the West Shore, by Cleaver, overlooks Abigail’s connection to the magazine. [↩]

- Circulation peaked at 15,000, circa 1889, after which revenues began to decline (Cleaver 216). Turnbull suggests that financial woes contributed to Samuel’s decision to quit his enterprise for the insurance business (168). The West Shore’s new officers were headed by Joseph Franklin Watson, a prominent industrialist and banker who had arrived in Portland from Massachusetts in 1871, was vice-president of the Smith and Watson Iron Works, and became general superintendent of the Oregon Iron and Steel Company at about the time he acquired an interest in the paper (Gaston, Portland 2: 472-74; Who was Who 1308). Other officers included E. A. King and H. C. Wortman (of Olds, Wortman, and King department store fame); directors included Charles E. Ladd, Herbert Bradley (both also directors of the North Pacific Industrial Association), and T. F. Osborn. Apparently J. M. Lawrence joined later, possibly replacing King (Cleaver 216, 223 [n. 70]).

Scott Duniway never would have allied with Samuel’s original paper. In its early years, Abigail and her New Northwest offended the West Shore’s sense of decorum. In July, 1879, replying to her account of a visit in Jacksonville, in southern Oregon, during which she was egged and hung in effigy, it editorialized that, “being of the weaker sex,” “Mrs. D.” had been let off lightly. Although expressing admiration for her “grit,” it complained that she took advantage “rather too often of the fortunate circumstance of being born a woman” and scolded: “As her paper . . . is taken mostly in families where the young folks are liable to read it, we have a right to demand that it be edited with a little more decency than what would be expected from a pothouse politician.” Whether the West Shore’s new managers had more than a financial stake in the popularity of the gospel of woman’s rights is undetermined.

The Woman’s Journal reported Abigail’s new venture on May 2, 1891, commenting that her department “shows all Mrs. Duniway’s old editorial vigor.” [↩]

- February 28: “Hobby Horses and Their Riders” (part two). March 7: “A Transcontinental Tour.” March 14: “Women and Preachers as Financiers.” March 21: “Women’s Week in Washington.” March 28: “The Last Hours of Congress.” April 4: “The Ferment of Politics.” April 11: “The Cornell Road” (fiction). [↩]